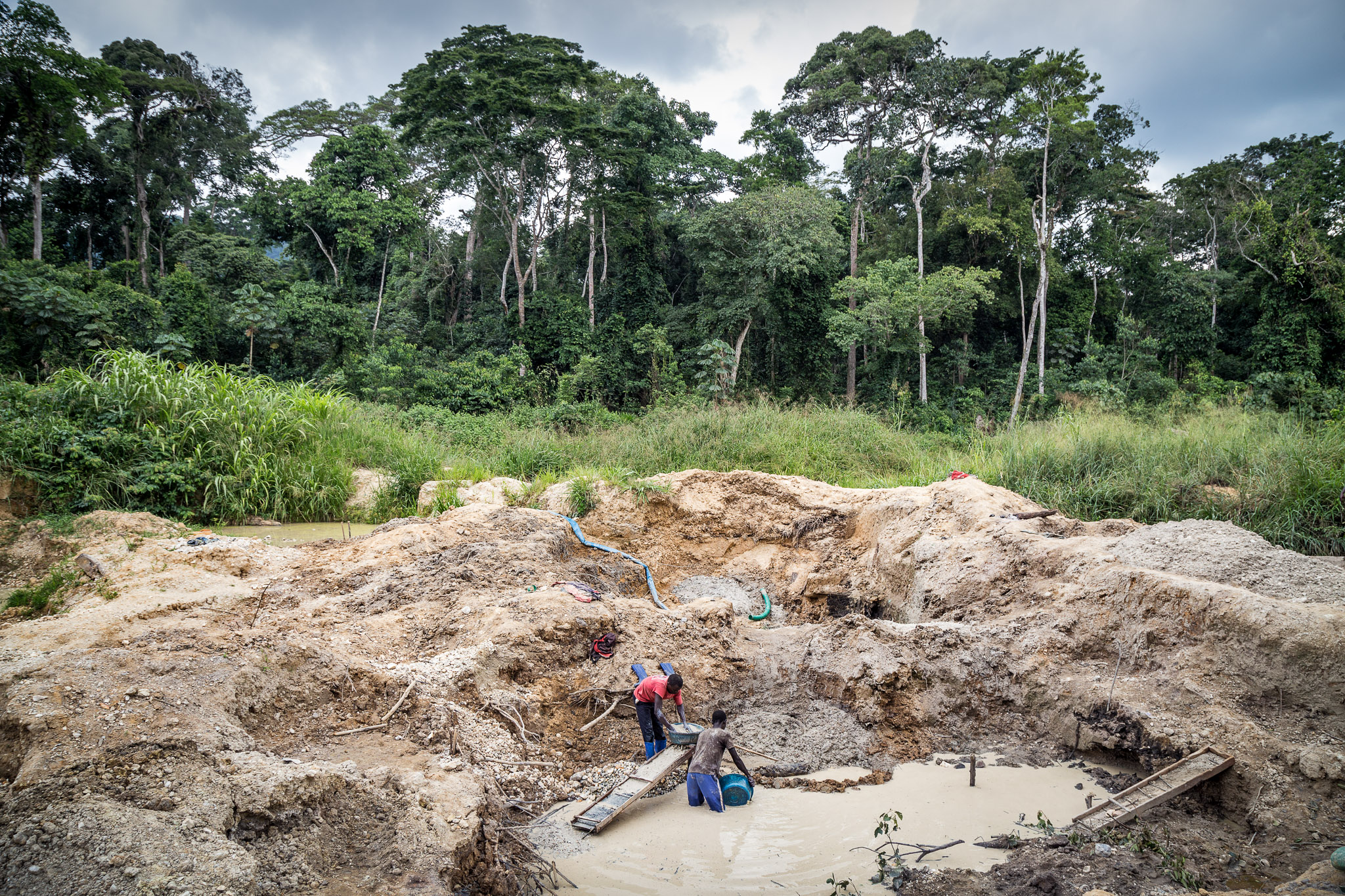

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has long been at the center of global debates over conflict minerals. As the country faces another crisis within its mineral-rich regions, analysts often offer quick solutions without diving into local needs or learnings from the past.

One suggested solution which has been attempted before, is imposing an embargo on all mineral exports or mining activities. While this might seem like a straightforward solution, it overlooks the complex realities on the ground. Experience and insights from those directly involved in the sector reveal that such measures often come with unintended consequences. Instead of addressing the underlying issues, embargoes can intensify the challenges faced by the local population, ultimately undermining efforts to improve their situation.

Past Supply Chain Interventions

Numerous organizations—including IMPACT—have dedicated years to understanding and addressing the multifaceted issues of violence and mineral smuggling in DRC. Effective responses must be informed by this extensive learning rather than driven by reactive measures. Quick fixes like embargoes disrupt the livelihoods of local communities that rely on artisanal mining, pushing them deeper into poverty or illegal networks. Instead of alleviating the situation, these measures can intensify the hardships faced by the very people they aim to help.

History provides valuable lessons on the impact of broad, reactionary policies.

In 2010, Dodd-Frank Act’s Section 1502 required U.S.-publicly listed companies to report tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold in their supply chains sourced from DRC or neighbouring countries. While it did not discourage sourcing, it required companies to undertake due diligence to ensure they did not fund armed groups with their sourcing. However, when the act came into effect, many companies, fearing non-compliance with the law or potential reputational damage, stopped sourcing minerals from DRC and the surrounding region altogether. This de facto boycott intensified the situation— causing economic distress for local mining communities and pushing many artisanal miners deeper into poverty.

As a result, armed groups began to rethink their strategies as they grappled with the shifting economic landscape. Initially, these groups thrived by trafficking, taxing, and directly controlling tungsten, and tantalum (3Ts) at or near mining sites. This approach not only provided them with a steady revenue stream but also incentivized them to maintain a certain degree of stability and safety in these areas. However, as their earnings from these minerals declined, the groups were driven to seek alternative sources of income.

Reports reveal that as the profits from the 3Ts dwindled, groups shifted their attention to gold. Traceability did not yet exist for artisanal gold and prices for the mineral had skyrocketed. This led to fierce competition over gold-rich regions, further escalating conflict and deepening the cycle of exploitation.

The Adaptability of Mineral Smugglers

Firsthand experience shows that embargoes can lead to a surge in the black market, where minerals are smuggled out of the country under more dangerous and exploitative conditions. For instance, in October 2019, the US Customs and Border Protection Agency announced additional checks on artisanal gold from the DRC due to reports of forced labour. DRC’s civil society however, called it a stigma that would result in a “de-facto embargo” and only increase smuggling. The outbreak of COVID-19 further intensified these dynamics. During the pandemic, borders were essentially closed, and formal trade routes were severely disrupted. IMPACT’s research during COVID-19 revealed that these restrictions created ideal conditions for the black market to thrive. With legal routes blocked, smugglers took advantage of the chaos and reduced oversight to increase their operations. Traders leveraged the crisis to bypass formal checkpoints and move minerals through unofficial, often more risky routes.

A critical insight from our work in the DRC is the adaptability of mineral smugglers. Driven by profit, these individuals and networks are skilled at bypassing restrictions and regulations. They exploit loopholes and adapt to new restrictions with ease, making it challenging to curb their activities through straightforward bans. Smugglers quickly find alternative routes and methods to transport minerals out of the country, leveraging their deep knowledge of the local terrain and complex networks. This flexibility allows them to continue profiting from the illicit trade, even in the face of increased enforcement efforts. According to IMPACT’s findings, when authorities intensify crackdowns, smugglers respond by relocating their operations to new jurisdictions where oversight is weaker or can be evaded more easily. They reconstitute their organizations, often changing the names of their companies and installing new individuals as the ‘face‘ of the business to avoid detection. These entities exploit loopholes in local and international laws, taking advantage of the fragmented regulatory environments across borders. By doing so, they maintain a continuous flow of minerals out of the country.

Further, smugglers exploit the economic vulnerabilities of local communities by encouraging artisanal miners to sell their minerals outside legal channels, creating a cycle of economic dependency that is difficult to break. These miners often receive inventory financing from smugglers to cover the costs of mining and basic needs before finding gold, making them financially indebted to the smugglers. This dependency makes it challenging to transition miners to a formal model, undermining efforts to establish responsible sourcing practices and further cementing illegal trade.

Barriers to Removing Black Market Minerals

Eliminating black market minerals, especially in the gold sector, is a complex challenge with numerous barriers. One major obstacle is the insufficient number of validated conflict-free sites from which gold can legally be extracted. Additionally, inadequate or inconsistent inventory financing presents a significant challenge, as artisanal miners often struggle to access necessary funds—forcing them to sell their gold through unofficial channels where smugglers offer immediate payment and sometimes a higher price. High taxes and transportation costs complicate the legal gold trade, making the black market more appealing. Economic pressures, and DRC’s lack of infrastructure further intensify these barriers, making the transition to legal mining and trading practices challenging.

Working with Local Communities

It’s crucial to be fully committed to listening to and empowering local communities. Rather than imposing external solutions, it’s essential to understand the perspectives of those who live and work in these areas, particularly the women who are often left out of discussions and efforts to address conflict. IMPACT’s Women of Peace project exemplifies how community-led initiatives can create meaningful change. Through the project, women in DRC were trained and supported to take on leadership roles in their communities, helping to mediate conflicts, promote peace, and advocate for the rights of their fellow community members.

In Ituri Province, women formed Peace Hubs that actively work to resolve disputes before they escalate into violence. These Hubs also play a crucial role in raising awareness about the impact of armed groups on their communities and in advocating for the protection of women and children. By centering the voices of women and other community members, strategies can be deployed that are both culturally sensitive and tailored to the actual needs of the people.

Listening to these local voices helps us identify the root causes of conflict and understand the community’s needs. It’s through this collaborative approach that more sustainable and effective interventions can be crafted. When local communities lead, the outcomes are more likely to be embraced and maintained over the long term.

As part of these efforts, it’s important to consider how we can support responsible and resilient supply chains that are less vulnerable to armed groups. This means working with artisanal miners and communities in ways that meet them where they are, rather than focusing solely on the demands of the international market or external standards.

Supporting these communities involves providing education, economic opportunities, and access to resources that enable them to participate in the legal economy on their own terms. For example, the Women of Peace partners had a parallel project to support women in developing complementary livelihoods, such as small-scale agriculture or trade, which reduces their reliance on mining and the risks associated with it. By building these connections and ensuring that the community has the tools and knowledge they need, we can help create supply chains that are not only transparent and traceable but also rooted in the well-being and empowerment of the people who are most affected by the challenges in DRC.

Decades of Learning

Addressing mineral smuggling and violence in DRC requires a deep understanding of the systemic challenges contributing to decades of ongoing conflict. Minerals are not the root cause of violence but rather have become an instrumental source of financial gain and political power for many actors involved in the conflict in DRC and throughout the region.

While logic may tell us that cutting off that financial lifeline will lead to the disintegration of armed groups across the country, history and experience show us a different picture. One that sees those targeted by embargoes adapt their strategies or protect the status quo, while hundreds of thousands of artisanal miners and their families bear the brunt of the impact.

To meaningfully break the link between minerals and the conflict in DRC, we must address the root causes of conflict with more holistic approaches that go beyond mineral supply chains. It’s important to learn from past mistakes and avoid replicating failed attempts—simplistic solutions like embargoes are not the answer. We need to listen to the voices on the ground, support community-driven initiatives, and address the systemic challenges at the heart of the issue.

Interested in learning more?

Report: Illicit Gold Trade Thrives with Impunity in the Democratic Republic of Congo

How Taxation Discourages Legal Trade in DRC: Opportunities for Reform

How Peace Hubs can Improve Women’s Security in Mining Communities